I recently stumbled upon the practice of keeping a commonplace book and I haven’t been able to get it out of my mind since. I was struck by how it seems to embody the natural messiness of life and support the growth of a person in an indirect and gentle way.

I’ve been journaling in one way or another since I was 12 and I thought I exhausted all the ways in which this practice could benefit me. That is until I discovered the lost art of commonplace books. Perhaps what intrigued me the most is its unpretentious nature and free spirit. This practice is forgiving, yet unapologetic. I’ll explain later.

Although it’s an old method, its relevance hasn’t faded, it still shines like an old jewel. It has survived the centuries precisely because it’s an inexhaustible fountain of wisdom and introspection.

Let me introduce you to the magical world of commonplace books.

What is a commonplace book?

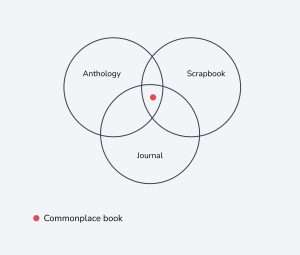

A commonplace book sits at the intersection of a scrapbook, an anthology and a journal.

It’s similar to a scrap book because it can contain a mosaic of ideas, compiled from different sources.

It’s similar to an anthology because it features a collection of ideas organized under the same topic.

It’s similar to a journal because it tells the story of us.

Popular entries may include quotes, maxims, prayers, recipes or observations (and many more other things).

Commonplacing is an indirect way of telling a story. Traditional journaling extracts the facts-of-the-matter, while commonplacing is concerned with the more subtle qualities of our experience. It reveals truths about ourselves without us having to spell it out.

History of the commonplace book

Commonplace books have probably emerged out of a method popular in the 8th century C.E., called florilegium (literally meaning gathering of flowers), which entailed the collection of passages from religious texts, used by their authors to create sermons.

Over the centuries, commonplace books grew in popularity and extended past the strict religious context. During the Renaissance, writers, theologians, philosophers or artists in general used commonplacing as a learning aid.

The philosopher John Locke wrote the first book on commonplacing in 1685, named A New Method of Making Common-Place-Books. Locke gave specific advice on how to arrange material by subject and category, using such key topics as love, politics, or ethics.

The Irish philosopher George Berkeley (1685-1753) used a commonplace book to develop his thoughts and arrive at a final version of his theories, which resulted in 2 books: New Theory of Vision and Principles of Human Knowledge. By examining his commonplace book, we can observe how his ideas have changed and matured over time.

Another figure who kept a commonplace book was the English astronomer and physicist Edmond Halley (1656-1741), whose manuscript hasn’t been examined until 1950s. The scholars who inspected his commonplace book found records of books Halley read (from antiquity until the 17th century), most of which influenced his work, maxims, commentaries on prose and literature, scientific subjects and more.

Over time, the function and structure of a commonplace book shifted and took many forms, going from a hub of daily thoughts and recorded maxims, to a more organized project, with clear goals. These books can have a common theme (quotes from book read) or combine multiple themes.

These books were perhaps humanity’s response to information overload. They acted as a repository of knowledge, an index of concepts and definitions. They helped their owners cultivate a better character by reminding them of important maxims, strengthen their faith through learning the scriptures or praying, learn new concepts and develop their ideas.

Philosophy behind the commonplace book

It’s an indirect way of telling a story. Traditional journaling extracts the facts-of-the-matter, while commonplacing is concerned with the more subtle qualities of our experience. It reveals truths about ourselves without us having to spell it out. The lyrics of a song you wrote down can hint at your predisposition, the books you read and record can indicate your passion, the maxims you jot down can allude to the things you needed to remember the most at a particular time.

What did I mean by “forgiving, yet unapologetic”? The forgiving part alludes to the loose and exploratory nature of a commonplace book, while the unapologetic aspect of it illustrates its tendency to reflect our deepest passions.

Benefits of a commonplace book

Reflection companion

It will refine your introspection skills and make you more aware of what preoccupies your mind. This process can be a two-way street: either something you notice in the world makes you add it to the commonplace book, or something you recorded already can spark reflections.

Inspires creativity

This type of book can act as a catalyst for your creative endeavors, because all the information you feed it can coalesce into new ideas and novel connection between subjects.

Catalogue of your interests

It can help you remember what caught your attention or what you were engrossed into at a particular time in your life. With a commonplace book, you’ll open a portal into your own mind.

Deepen your understanding of a subject

Commonplace books can be a terrific learning companion, helping you synthesize ideas, consolidate knowledge, record and comment on the research you’ve done, gather all the threads in one place.

Purpose

A commonplace book can serve as a vehicle for exploration, learning and growth. You may start with a predetermined goal and structure in mind, but it’s equally valid to just let the topics arise organically.

What to include

Let us take down one of those old notebooks which we have all, at one time or another, had a passion for beginning. Most of the pages are blank, it is true; but at the beginning we shall find a certain number very beautifully covered with a strikingly legible hand-writing. Here we have written down the names of great writers in their order of merit; here we have copied out fine passages from the classics; here are lists of books to be read; and here, most interesting of all, lists of books that have actually been read, as the reader testifies with some youthful vanity by a dash of red ink. 1Virginia Woolf, “Hours in a Library”

Here are some ideas of what’s usually found in a commonplace book.

- Information that peaks your interest

- Books your read

- Quotes: lines from books or articles, from movies or TV

- Thoughts sparked by a conversation

- Maxims

- Poems that touch you

- Lists of whatever kind (cities/countries visited, movies seen, games played, etc)

- Short reflections on life

- Lines from songs stuck in your head

Comparing commonplace books to other methods

There are some differences between a commonplace book and other information management methods, such as bullet journaling, a personal knowledge management system or simply keeping a notebook.

One important feature of a commonplace book is the fact that it’s (usually) analog. You can’t just copy-paste text or an image from the internet onto it. If you want to save a drawing or a chart, you have to draw it yourself. If you wish to collect a certain quote, you must write it by hand. This act of active engagement is a crucial part of the spirit of a commonplace book. It encourages reflection, deliberation and dynamic relationship with the material saved. Studies show that handwriting is conducive to learning and better retention.

Unlike a personal diary, a commonplace book doesn’t have an explicit narrative. There may be a story you can distinguish based on the material collected, but it’s more subtle. Your feelings and state of mind may be inferred

Keeping a commonplace book feels like a kinder way to grow, by wrestling with the articulations of others in the open as I hopefully adjust myself within.2Charley Locke, “Commonplace books are like a diary without the risk of annoying yourself,” New York Times

How to start a commonplace book

By now, it should be fairly obvious that starting a commonplace book doesn’t require any elaborate planning. All you need is a pen and a good quality notebook and you’re good to go. What you decide to include depends on your interests and preoccupations. If you’re an avid reader and would like an old school way of cataloguing your reads you can include them in your commonplace book.

The subjects can be as narrow or diverse as you wish.

Let the media you consume and your particular interests shape the process. You could focus on only one topic and populate your notebook with references relevant to it, such as ideas from online articles, quotes from books, mentions in popular culture. Or you could embrace a multi-disciplinary path and record any bits of information that make your brain’s cogs spin.

Don’t forget that the information you choose to exclude is as important as the one you choose to include. It’s entirely up to you how you curate the knowledge inside. Perhaps you’ll opt to reserve the more elaborate thoughts for your personal knowledge management system or another journal, and only include the highlights in your commonplace book.

Regarding organization, you can create different themes, as John Locke advocated:

If I would put anything in my Common-place Book, I find out a head to which I may refer it. Each head ought to be some important and essential word to the matter in hand; and in that word regard is to be had to the first letter, and the vowel that follows it; for upon these two letters depends the use of the index. 3John Locke, “A New Method of Making Common-Place-Books”

Additionally, an index would prove useful at the beginning of your notebook, especially if you cover many topics.

Footnotes

- 1Virginia Woolf, “Hours in a Library”

- 2Charley Locke, “Commonplace books are like a diary without the risk of annoying yourself,” New York Times

- 3John Locke, “A New Method of Making Common-Place-Books”